INSIGNIS Technology Corporation

So, why not move to NVMe?

The improvements in the storage interface, such as quadrupling of SATA bandwidth, isn’t the reason that SSDs are so much faster than HDDs. SSDs are faster because the latency or response time of the storage media improved by 1000x from a mechanical drive to an SSD.

The observable system performance, what the user can see and feel, is limited by a bottleneck. For the longest time that bottleneck has been the mechanical hard drive. Once that was removed the next bottleneck was the SATA-I interface. Now with SATA-III SSDs the bottleneck today might be some other part of the system, perhaps the GPU for graphics performance or the CPU or memory for processing performance, and in some cases, it might also be the storage system. If you are running storage intensive operations, then NVMe might be exactly what you need. But if the performance bottleneck is elsewhere, or if you don’t want to burden yourself with the higher power that comes with NVMe performance, then maybe NVMe is not what you are looking for right now.

The bottom line is that the incredible performance improvements realized by moving from mechanical storage to solid state are not going to be repeated by moving from SATA to NVMe. If the application doesn’t need the additional storage performance, then no benefit will be realized.

Why NVMe will take over … eventually

NVMe will become the de facto standard not because of the performance that it offers, but rather because of standardization and broad use. These transitions that are not performance driven can take a very long time to complete. Today traditional storage requires an ACHI (SATA) or SAS controller to connect mechanical hard disks to the PCIe bus, and NVMe is the solution that eliminates the bridge and instead makes the direct connection. But like many entrenched standards the SATA interface is well established, has multiple IP suppliers and is widely available with market based pricing.

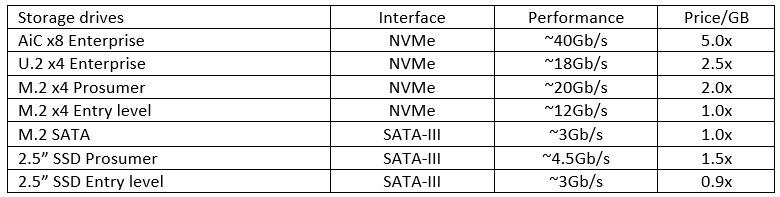

A quick survey of SSDs indicates NVMe prices are coming in line for entry level SSDs, but the high-performance potential of NVMe comes at a price. Looking at a range of 512GB SSDs shows the SATA and NVMe M.2s to be about the same price, yet still more expensive than the 2.5”. The premium is due to the performance and headroom of the M.2.

NVMe SSD form factors

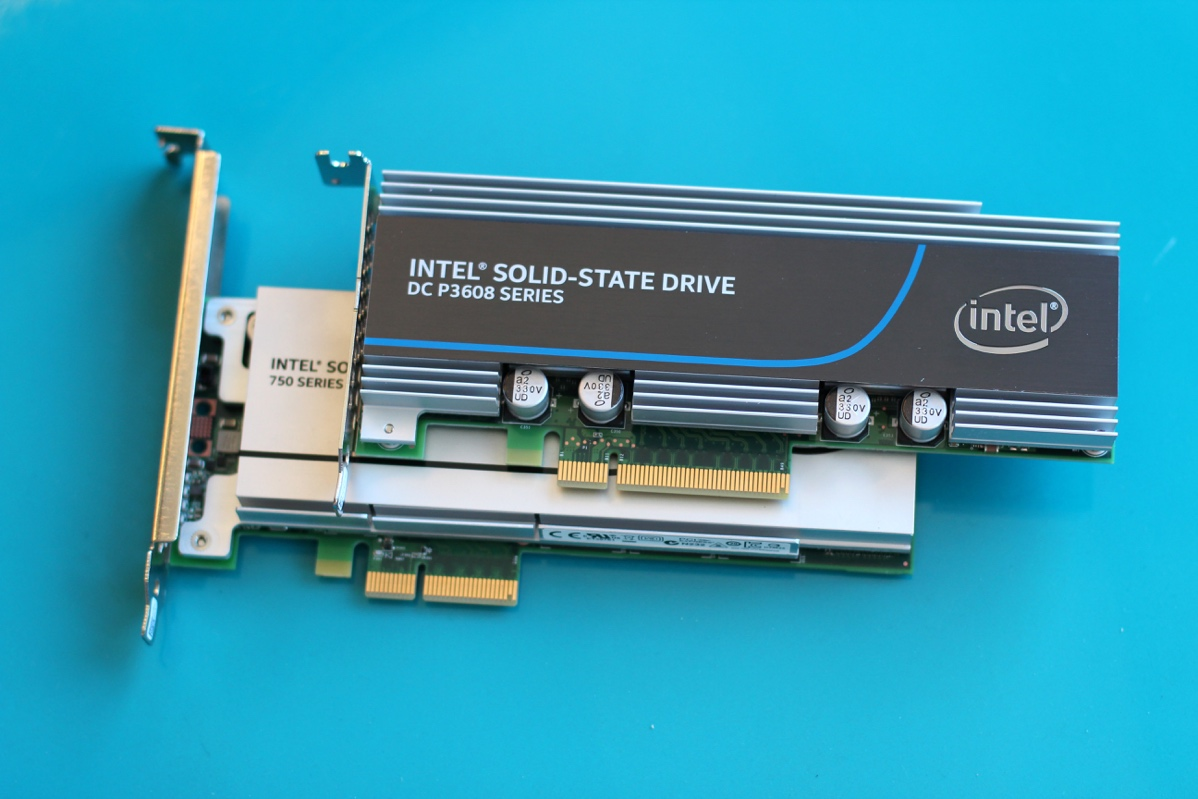

NVMe drives come in three basic form factors, the Add-in card (AiC), the 2.5” (U.2) and the M.2. Since NVMe protocol runs on the PCIe physical layer, the connections will be nearly identical to PCIe. The AiC cards resemble standard expansions cards, the M.2 resembles mini-PCIe, and the 2.5” is meant to address the modularity requirements of storage systems. The AiC is high capacity and can be designed to support any number of PCIe lanes. These cards are generally for high IOPS applications, but you need to dedicate PCIe slots for the cards and they are not hot swappable. Below are a 4 lane and an 8 lane AiC from Intel.

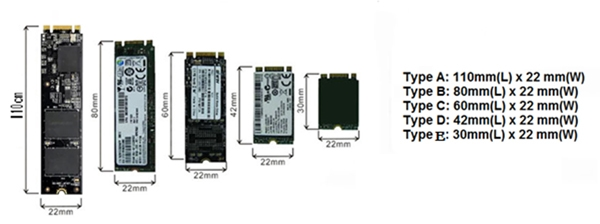

A smaller version of this kind of implementation is the M.2 form factor, commonly measuring 22mm wide and a length of between 42mm and 110mm. The M.2 socket resembles that of an SO-DIMM for memory, so the card lays parallel to the main board. Of course, there are other socket orientations available, but the most common is the one used in laptop computers.